Parsing Akili's Surprise FDA Clearance

Why did it take 2.5 years? What new data were presented to secure clearance? And how does the commercial opportunity look for Akili's product?

Before we get started, if you want to follow along with new digital health developments and more of my writings:

And with that, let’s get to the fun.

Earlier this week, Akili announced that their novel digital therapeutic for ADHD, EndeavorRx (AKL-T01), had been cleared by the FDA. While this is undoubtedly an important moment for the field of digital therapeutics, those who have been following the Akili story know that EndeavorRx has been under FDA review for 2.5 years (since late 2017), ~ 5 times longer than the average medical device review process. This week’s surprise clearance raises a host of interesting questions — what were the FDA’s concerns with Akili’s initial application, what new data did Akili present to secure the clearance, and how does the commercial opportunity look for Akili’s innovative technology?

Background

Akili was founded in 2011 on the idea that video games could be used as a delivery mechanism for engaging and effective digital treatments. The technology was first evaluated for improving cognitive control in older adults, and later repurposed for the treatment of ADHD in children. The ADHD therapeutic, EndeavorRx, is a video game that requires users to perform two tasks in parallel — a perceptual discrimination targeting task (see below) and a sensory motor navigation task (similar to driving). The game adjusts its parameters in real-time based on the user’s performance and tracks usage and progress. To date, Akili has raised about 140 million USD.

An example of a perceptual discrimination task in EndeavorRx:

Akili has published 4 peer-review papers to date on EndeavorRx (also known as Project: EVO during development), including 3 open-label trials and 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT), better known as the STARS-ADHD trial. Since the FDA submission would have centered around the RCT, I’ll start there to discuss potential concerns the FDA may have had with Akili’s initial application.

STARS-ADHD Trial

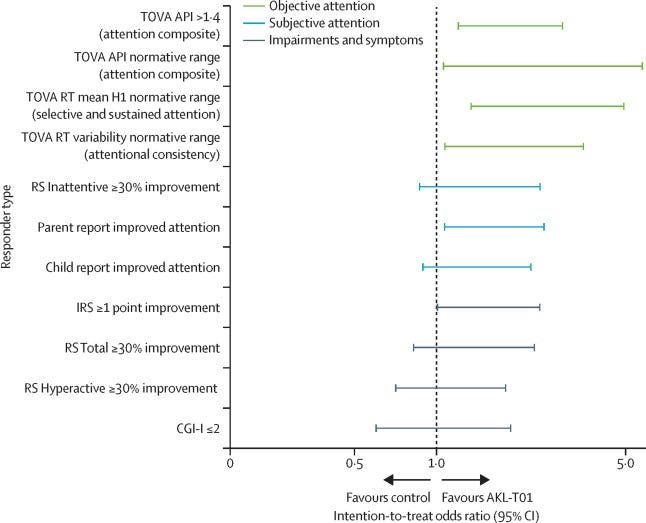

The STARS-ADHD Trial was a randomized controlled trial comparing the safety and efficacy of EndeavorRx to a digital placebo control for the treatment of ADHD in children aged 8-12. Overall, the trial was well-designed — the sponsor, parents, patients, and investigators were masked to treatment group assignments, the study was adequately powered, and the endpoints were prospectively established. The trial achieved its primary endpoint, as there was a significant difference between groups in mean change on the Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA).

However, the study also had several key limitations that could have been questioned as part of the FDA review process.

(1) The study failed to achieve its secondary endpoints, as there was no difference between groups on the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS), ADHD-Rating Scale (ADHD-RS), or Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF). In a typical RCT for FDA submission, achieving the primary endpoint alone would be sufficient for clearance, but this case is trickier because Akili chose a non-standard primary endpoint by using the TOVA. In fact, in May 2019, FDA released a guidance on developing drugs for ADHD that included a list of acceptable primary endpoint measures which did not mention the TOVA. The only measure cited by the FDA that was used in the STARS-ADHD trial was the ADHD-RS; therefore, the fact that EndeavorRx was not able to demonstrate efficacy on the ADHD-RS almost certainly became a sticking point during FDA review.

(2) The study duration of 4 weeks was relatively short, especially when paired with the fact that the study did not evaluate long-term durability. Given that ADHD is managed as a chronic condition, outstanding questions around treatment duration and long-term durability would have been important for the FDA to resolve.

The STARS-ADHD trial was completed in Aug 2017 and Akili submitted their application to the FDA on late 2017 / early 2018. Since the review process from then until now is a black box, we have to dig into the approval notice released this week to hypothesize about FDA’s thinking and what happened during the 2.5 year review period.

FDA Approval Notice

The first thing to look for in any FDA approval notice is the Indications For Use (IFU), since it defines what a device can be used for and is expected to do. The IFU for EndeavorRx are as follows:

EndeavorRx is a digital therapeutic indicated to improve attention function as measured by computer-based testing in children ages 8-12 years old with primarily inattentive or combined-type ADHD, who have a demonstrated attention issue. Patients who engage with EndeavorRx demonstrate improvements in a digitally assessed measure Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) of sustained and selective attention and may not display benefits in typical behavioral symptoms, such as hyperactivity. EndeavorRx should be considered for use as part of a therapeutic program that may include: clinician-directed therapy, medication, and/or educational programs, which further address symptoms of the disorder.

First, a couple of points are unsurprising. The IFU specifies that EndeavorRx should be used for children ages 8-12, which matches the age cohort in the STARS-ADHD trial. Especially for pediatric populations, the FDA tends to err on the side of caution and only provide clearance for the age cohort that has been studied, rather than assume safety and efficacy for a broader age range. The IFU is also very particular about the fact that EndeavorRx can improve attention function “as measured by computer-based testing”, and demonstrate improvements in a “digitally assessed measure TOVA”, confirming my earlier suspicion that FDA would raise concerns about the non-standard primary endpoint used in the STARS-ADHD trial.

One part of the IFU that is surprising is the fact that it does not contain limitations around long-term durability. With the few other digital therapeutic clearances to date, the FDA has been explicit when long-term durability is unknown (e.g. with Pear Therapeutic’s reSET clearance: “the benefit of treatment … was not evaluated beyond 12 weeks”).

Nevertheless, the main part of the IFU that sticks out is the last sentence, which states that EndeavorRx should be considered as an adjunct to other established treatments. While this doesn’t seem unreasonable on the surface, it is surprising given that the STARS-ADHD trial studied EndeavorRx as a standalone treatment, not as an adjunct. FDA’s view of EndeavorRx as an adjunct treatment is reinforced in the device classification description (“software intended to provide therapy for ADHD … as an adjunct to clinician supervised treatment”) and again in the special controls (“labeling must include a warning that the digital therapy device is not intended for use as a standalone therapeutic device”).

Looking back at the STARS-ADHD publication, the only mention of other treatments is a post-hoc analysis of a subgroup who recently discontinued stimulant medications. Unlike the full patient population, this subgroup did achieve a significant difference between groups on most secondary endpoints, including the ADHD-RS.

Assuming that the FDA would not approve EndeavorRx with an IFU not supported by clinical data, we are clearly missing a piece of the puzzle. Perhaps what happened is that the FDA deemed Akili’s initial data was insufficient, given that the TOVA is a non-standard primary endpoint and the study failed to achieve success on more well-accepted endpoints. However, data from the subgroup I just mentioned may have prompted Akili to reposition the device as an adjunct treatment and obtain additional clinical data to support this claim. A subsequent clinical trial(s) would explain the lengthy delay in EndeavorRx’s review process as well.

Unpublished Studies

From searching on ClinicalTrials.gov, we find that Akili has conducted two further clinical trials on EndeavorRx since the STARS-ADHD trial that have not yet been published. One of them (NCT03649074) evaluated EndeavorRx as an adjunct to stimulant medication and ended in Feb 2020, which lines up well with this week’s clearance. Importantly, this study also used a different primary endpoint — the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS) instead of the TOVA — perhaps as a way to remedy the primary endpoint concerns from the STARS-ADHD trial.

The second unpublished study (NCT02828644) evaluated the durability of EndeavorRx’s treatment benefit, solving the other limitation I highlighted with the STARS-ADHD trial. This study ended in Feb 2019, which would have given Akili plenty of time to submit the data to the FDA to alleviate their concerns and remove any mention of durability issues from the IFU.

Given all this, it seems likely that Akili’s initial FDA submission for EndeavorRx as a standalone treatment was deemed insufficient, due to the non-standard primary endpoint used in the STARS-ADHD trial, the failure to achieve important secondary endpoints, and the outstanding question of long-term durability. Based on the data from the STARS-ADHD trial, Akili decided to reposition the device as an adjunct treatment, and conducted two follow-up studies evaluating the device’s efficacy on top of medications and the durability of treatment benefit. With the additional data in hand, Akili was ultimately able to secure FDA clearance, albeit as an adjunct instead of a standalone treatment.

Turning to the future, given Akili’s clearance and the final IFU for EndeavorRx, what does the commercial opportunity look like for the technology?

Commercial Opportunity

The broad commercial opportunity is substantial — the market size for ADHD is estimated to be almost $25 billion by 2025 with a 6.4% CAGR. But how much of the total market will Akili and EndeavorRx be able to capture? As with all novel treatments, the commercial opportunity for EndeavorRx will be driven by (1) physician adoption and (2) payer coverage. Let’s start with physician adoption.

Since Akili had to settle for clearance as an adjunct rather than standalone treatment, there is little chance EndeavorRx will become a new standard of care or first-line treatment for the near future. Instead, Akili may choose to focus initially on the patients with the highest unmet need — treatment-resistant patients where existing medications are insufficient. Physician adoption will likely be easiest for these patients, given the lack of other options. Indeed, Akili does seem to be moving in this direction, as one of their recent unpublished studies was focused on enrolling patients on stimulants who were “inadequately managed” by stimulants alone. Importantly, however, that this strategy does cut Akili’s addressable market significantly right off the bat, as only ~30% of ADHD patients are treatment-resistant.

Another patient cohort where physician adoption may be easier is in younger patients, since physicians are more reluctant to prescribe medications for this age group. For children younger than 6, ADHD medical guidelines instruct physicians to start with behavior therapy alone, and only add medications if behavior therapy is ineffective. However, this may be a tricky approach in the near-term; because the clearance for EndeavorRx was for 8-12 year olds, physicians would have to feel comfortable prescribing the device off-label for younger children. A label expansion study followed by a second FDA submission may be needed for Akili to capture this market.

To obtain payer coverage, Akili will need to present a compelling story around unmet medical need as well as cost savings. With treatment-resistant patients, the medical need will be as clear to payers as it is to physicians, and will outweigh the importance of cost savings. If payers take a conservative approach, they may require patients to demonstrate failed efficacy with medications first before paying for EndeavorRx, but it will be hard for them not to cover a new modality with proven outcomes in patients with no other options. With the remaining patients, the cost savings story will be critical for Akili to obtain coverage. One approach would be to show that using EndeavorRx in combination with medications allows you to reduce stimulant dosing, saving money and also reducing the risk of adverse outcomes and costly complications. Another approach would be to evaluate whether remote monitoring of treatment with EndeavorRx could decrease physician follow-up visits and costs to the system as a whole. A series of health economics studies conducted in collaboration with major payers would help answer these key questions.

Akili’s FDA clearance of EndeavorRx is an exciting development for a field that used to see regulatory approval as the biggest question mark in creating a new digital therapeutic. But Akili’s successes or failures with commercializing EndeavorRx in the coming years will determine whether digital therapeutics are still too early, or finally here to stay.